The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology of the University of Pennsylvania’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design brings environmental and social scientists together with planners, designers, policy-makers, and communities to develop practical, innovative ways of improving the quality of life in the places most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

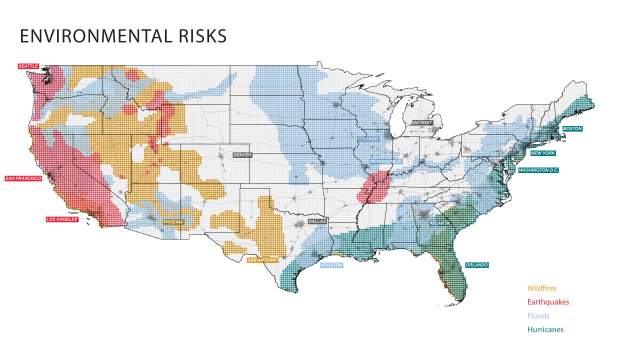

The 2100 Project: An Atlas for the Green New Deal was conceived in relation to three intersecting issues. First, excess carbon in the atmosphere is changing the world’s climate; sea levels are rising, temperatures are increasing, and destructive weather events are becoming more frequent. Second, because our systems of extraction, production and consumption are causing climate change, an incremental approach to the future is not an option. Third, the US population is expected to grow by at least 100 million people this century, adding significantly to what is already the world’s most consumptive, high-carbon economy.

Taking on these challenges requires that we ask some big — and unsettling — questions. What will be lost — economically, culturally, psychologically, physically — should the climate crisis continue unabated? How can we begin to come together around a response to the crisis that will reshape how and where we live? How can we begin to think about investments in the built environment as a catalyst for the broader aims of decarbonisation, adaptation, and social justice at a meaningful scale?

The Green New Deal does not pretend to have all the answers, but it’s a bold and necessary start. Because it connects social change with environmental change, and because it recalls the ambitious spirit the original New Deal, the Green New Deal is the only set of ideas on the table that are scaled to the challenges we face. If realised, the Green New Deal would revolutionise our systems of production and transform how and where we live. If realised, the Green New Deal would enable us to not only adapt to climate change, but to also mitigate its root causes.

But right now, the Green New Deal is embryonic, represented only in the most abstract set of goals outlined in H.R. 109. Its outline of a sustainable future needs to be filled in. It needs to be developed, debated and designed. To that end, this Atlas for a Green New Deal brings together a vast and disparate array of information in the form of maps and datascapes; tools to help us understand the spatial consequences of climate change—not so that we may be frightened by them, but so that we may be mobilised around a response to them.

As the authors of the first instalment in The 2100 Project, An Atlas for the Green New Deal, we became interested in assembling this phase of research for three primary reasons. The first relates to the idea of back-casting as it pertains to the principal historical analogues of the Green New Deal: FDR’s New Deal and JFK’s Moonshot. We remain convinced that the window for massive, national-scale action on climate will open again soon, and we aim to use this project as a vehicle for generating new research into how those transformations might unfold. The second rationale for constructing this atlas is tied to the paucity of spatial expertise and imagination within the current Green New Deal movement. Though it has necessarily been led by organisers, economists, policy wonks, and others, the Green New Deal would transform how and where we live—it would revolutionise our buildings, landscapes, and public works in ways that have yet to be conceived. The Green New Deal is the biggest design and environmental idea in a century. As faculty and graduate students in a world-renowned school of design, we feel an obligation to engage in the Green New Deal along these lines. Finally, we felt compelled to assemble this atlas and to launch The 2100 Project in part because no one else has put anything like it together—all of the spatialised climate, land, and people-related models of the future in one place, synthesised and tightly curated, contextualised and coherently packaged together as an Atlas for the Green New Deal. And we also felt compelled to use this project as a way to critique the notion of precision and certainty embedded in these models by representing them through pixelated maps. After all, the future is fuzzy.

The 2100 Project, An Atlas for the Green New Deal, with detailed maps and issue discussions, can be found here: https://mcharg.upenn.edu/2100-project-atlas-green-new-deal.