Were ancient Aboriginal tracks and pathways the forerunners of some of our modern roads and highways?

By Tony Proust

My family has land at Numeralla on the Great Dividing Range about 30 kilometres northeast of Cooma in southeastern New South Wales. Some years ago, I casually mentioned this to a university academic who knows the Monaro well, and he immediately replied that Numeralla was on an Aboriginal ‘songline’. I was intrigued and initially filed this information away for reference, but it eventually got me thinking: What does this mean?

The land in question is adjacent to the Big Badja River which flows to the west from headwaters in the Great Dividing Range and ultimately discharges 1,000 kilometres west into the Southern Ocean. Meanwhile just to the east is the headwaters of the Tuross River which flows eastwards to the Pacific Ocean. I realised that its quite likely that in times past, Aboriginal people may have walked past this land on their annual treks to the south coast and back. They would have followed the river valleys linking the Monaro to the south coast and maybe there was a songline to help them along the journey. It all seems very logical.

We know that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people developed and used expert knowledge to navigate through country — for trade, to find materials for tools, to find seasonal foods and water, traditional medicines and for ceremonial reasons. They used geological features, water courses, trees, and the direction of sunrise and the stars to navigate across the landscape. In the process they created the ‘dreaming’ or songlines so that this information could be recalled and passed onto the next generation.

So, is there any evidence that a songline, which may have included an ancient track or pathway, created by thousands of years of walking, is reflected in our modern road network? I began my search and quickly identified some roads and highways that probably follow ancient Aboriginal tracks or pathways.

In 1796 the crew of a fishing boat wrecked north of the Hunter River at Port Stephens, walked to Sydney. They were guided the local Aboriginals along a coastal path to the Hunter River and from there onto connecting paths via Lake Macquarie and Broken Bay to the north shore of Sydney Harbour. They were probably escorted by those locals through the country, along ancient pathways, before being handed on to new guides as they proceeded south, ensuring their safe passage through neighbouring territories down the coast. Today the Pacific Highway linking Newcastle with Sydney may include some of these original tracks.

So what is a songline?

As described in the book Songlines edited by Margo Neale, songlines are a means of storing and learning knowledge, ancient and modern. They are stories embodied in the land, sea and skies to be remembered and passed on through song, dance, art, ceremony and, most importantly, through attachment to Country. A songline is a system for the retention and transmission of knowledge to enhance lives. They are not unique to Australian indigenous cultures — they are a feature of many traditional cultures.

Some songlines are confined to a small area and do not travel far. Other songlines are epic — they stretch across the entire continent like a web of interconnecting pathways encompassing multiple sites.

My thesis is that a songline would have included a trading route, track or pathway used to travel from place to place, depending on seasonal food sources and cultural practices. In a society with only oral traditions, a songline, possibly using mnemonic techniques, was a reliable way to teach the next generation how to get from place to place and how to find food and water on the journey, critical to survival in what can be a harsh landscape. Young children would have learnt a very basic songline, so they didn’t get lost, which became more detailed as they grew older. The Elders would have known a very detailed songline.

Superhighways of Sahul

Sahul is the name of the prehistoric mega-continent that once encompassed Australia, Tasmania and Papua New Guinea. The name first appeared on 17th-century Dutch maps of the sandbank between Australia and Timor. Humans colonised Sahul about 60,000 years ago.

Research conducted by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage identifies the paths that were likely trodden by the ancient Aboriginal people as they moved across the continent from the Kimberley to Tasmania. As recently as 12,000 years ago you could walk from the northernmost part of Papua New Guinea to the southernmost part of Tasmania. The researchers constructed “a digital elevation model for Sahul with a viewshed analysis and most efficient walking routes to create potential migratory pathways which revealed likely ‘superhighways’ crossing the continent — crosschecking the mapping with archaeological data confirming their analysis” (see Figure 1).

The most remarkable thing about the map in Figure 1 is how recognisable it is. From the Great Dividing Range along the east coast, to the Kimberley in the northwest and MacDonnell Ranges in the Red Centre. You can almost recognise our Highway 1.

Interestingly, Commonground.org.au, which seeks to help society understand First Nations knowledge and culture, explains that “songlines are passed from Elder to Elder over thousands of years. Many of the routes shared through songlines are now modern highways and roads across Australia. The famous route across the Nullarbor between Perth and Adelaide came from songlines as did the highway between the Kimberleys and Darwin”.

Hawkesbury to the Hunter

My first case study is the route between Sydney and Newcastle. Imagine walking from Wisemans ferry on the Hawkesbury River to Cessnock in the Hunter Valley, a distance of about 100 kilometres. You would be travelling through Yengo, now the Yengo National Park, which was a very important place for Aboriginal people. There are many traditional Aboriginal tracks through the area that would have provided trading routes for the locals between the Hawkesbury and Hunter rivers.

Nearly 200 years ago the colonial government decided to build a road, now called the Old Great North Road, from Wisemans Ferry on the Hawkesbury River to the Hunter. More than 700 convicts and their overseers constructed buttresses, culverts, bridges and nine-metre-high retaining walls over a ten-year period from 1825. What evidence is there that this road followed an ancient Aboriginal track? The page ‘Australian Convict sites – Old Great North Road’ on the website of Environment and Heritage (part of the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water) states the following:

The original line of the Old Great North Road was surveyed in 1825 by the colony’s Assistant Surveyor, Heneage Finch. It probably followed an Aboriginal travelling route, and local Aboriginal people may have purposefully diverted the European road surveyors away from their sacred sites.

We will never know for certain if the Old Great North Road follows an ancient track, but it is highly likely. We know the local people traded widely along tracks and pathways and that they walked from the Hawkesbury to the Hunter. I am confident if a surveyor was asked to find a route for a road from one place to another and found an existing walking track that suited the purpose, then it would have formed part of the survey. It is simply common sense.

Richmond to Lithgow

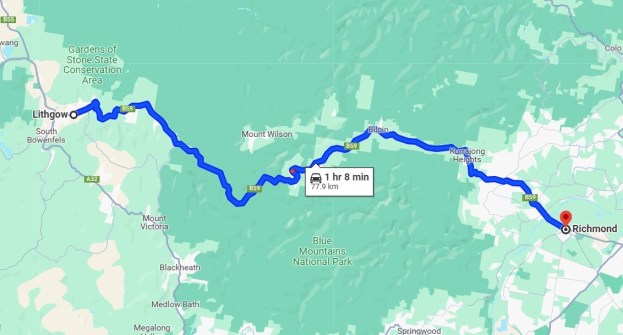

My second case study of an ancient Aboriginal track that became a road, is the Bells Line of Road across the Blue Mountains, linking Richmond with Lithgow.

It is well documented that the Bells Line of Road is part of an original pathway of the Darug people along Bilpin ridge, first shown to Europeans in 1823. Government surveyors mapped the ‘Bells Line’ and it was later cleared to become the second road crossing the Blue Mountains. There are references in early explorers’ journals that piles of rocks were observed along ancient Aboriginal walking paths, suggesting the locals removed the stones to make the walking easier. Anyone walking the same route regularly would do that. I was taught that Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth found the way across the mountains but in reality, they probably followed existing Aboriginal tracks along the ridgelines.

As we know from the Bells Line of Road case study and, I suspect, the Numeralla example above, ancient Aboriginal pathways and tracks, particularly those crossing mountain ranges along the east coast, most likely followed ridge lines to avoid rivers (except when required for food and water) because the walking was easier following the contours. Much further west they probably followed the inland rivers such as the Barka (Darling) while making sure not to interfere with the water and life along the waterways.

Perth to Albany

My third case study is the Albany Highway linking Perth to Albany in Western Australia in the land of the Noongar, the Aboriginal people of southwestern Western Australia. According to the Kaartdijin Noongar website (noongarculture.org.au) of the South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, the Noongar people travelled within their country to trade with other families. What is now known as the Albany Highway was once a Noongar track between families in Perth and Albany. Noongar people would often travel for hundreds of kilometres on foot between each family group.

The Albany Highway is virtually a straight line from Perth to Albany. As a university student in Perth in the 1970s I regularly drove along it to Albany to visit family. Little did I know I was following the footsteps of the Noongar.

Canberra to Cooma

Turning to the Canberra region and my fourth case study, the Monaro Highway linking Canberra and Cooma. The highway parallels the Murrumbidgee River, and it is logical that the traditional route for Aboriginal people to journey from the Canberra region to the Snowy Mountains to utilise seasonal foods would follow it. In her book The Road South, Ruth McFadden writes:

The Monaro Highway is an ancient track more or less north to south which was used by the Ngarigo, Ngunnawhal and Walgulu peoples since the dawn of time as they trekked annually each summer to feast on the Bogong moth in caves in the mountains. They left no footprints but gave us a multitude of wonderful names — Molonglo, Pialligo, Tharwa, Michelago, Timbrey, Umeralla, Kuma and Morombidgee among others.

It is reasonable to assume that the Monaro Highway follows an ancient songline.

I have lost count of the number of times I have driven the Monaro Highway, which is one of the most scenic road trips I know. I sometimes muse as to the untold number of people who made a similar journey before 1788, let alone since. In a good season with plenty of water in the creeks and an abundance of food, they would have taken the easier path across the famous treeless plains of the Monaro more or less directly to their destination and avoiding the Morombidgee (Murrumbidgee) when they could.

However in times of scarcity and drought they would keep close to the river, which was most likely the only reliable source of food and water. The walking would be harder and more time consuming.

I suggest that the current alignment of the highway is closer to the former pathway. I have no evidence for this yet, but it just seems logical to me.

Canning to Kimberley

Consider the famous outback stock routes: the Canning, Birdsville, Strzelecki and others. Stretching across Australia these routes are hardly new — they were traditional pathways for the Aboriginal people, marked and maintained for trade, travel and ceremonial purposes. Famous cattle empires were built on the backs of these ancient tracks.

For Aboriginal people the tangible aspects of these physical pathways were intertwined with their spiritual and cultural beliefs. The pathways were well known and signposted, running along watercourses and between water sources, following the easiest route through the landscape — through open areas, along ridgelines, and influenced by food and water sources. Those people navigated by the stars and had a vast knowledge of the land beyond their direct locality.

Alfred Canning was a famous Western Australian surveyor and explorer who created my fifth case study, the nearly 2,000-kilometre-long Canning Stock Route from the Kimberley to the railhead at Wiluna, more than 120 years ago. As described in the book On the Wallaby by Gerald Walsh, the route could only be used in good seasons. On the first droving trip south two stockmen were killed by the locals, who also vandalised some of Canning’s wells, many of which had been sunk by his team on ancient soaks critical to the local Aboriginals’ survival. (Once a soak was replaced by a well the locals could not access water as they did not have the required equipment: bucket, rope and pully. They were denied access to the water they had used for thousands of years; no wonder they vandalised the wells). Did Canning follow an ancient Aboriginal trading route and songline? Most likely.

Central Queensland

My last case study is the Carnarvon Highway in central Queensland. As documented in an article by Dr R.S. Fuller and published on the website of The Conversation, entitled ‘How ancient Aboriginal star maps have shaped Australia’s highway network’:

Aboriginal people have rich astronomical traditions but we know relatively little about their navigational abilities. It’s clear that ‘star maps’ are a means of teaching navigation outside of one’s own local country.

Star maps are a memory aid to teach the next generation how to find their way around Country. As Dr Fuller’s says, ‘songs are known to be an effective way of memorising a sequence in the oral transmission of knowledge’. The pattern of stars showed the ‘way points’ along the route, usually being waterholes and other features of the landscape, just as we use GPS today. One noted star map route ranged from Carnarvon Gorge in the north to Goodooga in the south and the Bunya Mountains in the east. The Carnarvon Highway generally reflects this star map and is probably described in a songline.

Conclusion

As historian Henry Reynolds explains, “early explorers were aided by well-trodden Aboriginal pathways, foot tracks, kept in good repair by fire. Travelling parties grew accustomed to finding foot tracks leading to water holes or wells. They learnt to recognise traditional pathways through dense forest and open grasslands created and maintained by fire. Following these travel corridors allowed easy movement through country”.

Finally, consider this description of a songline by a highly experienced land development professional who helped negotiate projects on Aboriginal land for many years:

Imagine an Aboriginal group who regularly travel between Kalgoorlie and Esperance — about 400 kms. They might navigate using large rock outcrops as landmarks or ‘way points’, creating a story — a songline — which is passed onto the next generation, about a giant who, back in the Dreamtime, strode across the landscape. The rock outcrops are the giants footprints. The songline guided them from one ‘footprint’ to the next, documenting water and food sources on the way.

If this journey is done twice a year for thousands of years, there will be a track or pathway… possibly two or three tracks, depending on availability of food and water. It is quite possible they had established camp sites along the way, which they would use year after year. It simply stands to reason.

It is clear that 60,000 years of Indigenous culture helped to ‘pave the way,’ almost literally, for the European settlement of our continent. It well accepted that, prior to 1788, Australia was crisscrossed by a network of traditional Aboriginal trading routes, tracks and pathways. Having made many road trips around this amazing country, I have no doubt that Aboriginal Australians have an extraordinary knowledge of our island continent, navigating far and wide using songlines and associated pathways and that many of our modern roads and highways follow these ancient tracks and trade routes.

This article is based the author’s own research as well as conversations with a range of others including Aboriginal elders, academics and experts. The author acknowledges the assistance of Dr Noel Nannup, past Elder in Residence at Edith Cowen University; Professor (Uncle) Ghillar Michael Anderson, A/Prof Southern Queensland University; and Dr Robert S. Fuller of Western Sydney University. The author can be contacted at asproust@tpg.com.au.