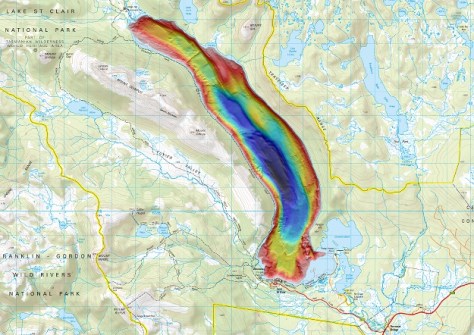

A CSIRO team has mapped the bed and shoreline of Lake St Clair in Tasmania’s central highlands, confirming it to be Australia’s deepest lake.

Previously it had been estimated that the lake’s maximum depth was between 160 and 215 metres, but nobody knew for sure.

Now, with a measured deepest point of 163 metres, it has been confirmed as the nation’s deepest lake… much deeper even than Bass Strait, which has a maximum depth of around 85 metres.

The team used Norbit multibeam systems provided by Seismic Asia Pacific along with LiDAR to produce the first high-resolution 3D map of the lakebed and shoreline respectively, revealing huge underwater cliffs, deep ravines and tall rock formations.

Lake St Clair was carved from the surrounding bedrock by glaciers and is renowned for its unspoiled beauty as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park.

CSIRO hydrographic surveyor, Augustin Déplante, said the mapping solves the mystery of the lake’s true depth.

“Our mapping confirms that Lake St Clair is absolutely Australia’s deepest lake, with the next deepest lake being less than 100 metres deep,” said Déplante.

“We found Lake St Clair’s deepest point is close to the western shore on the bend in the lake about 4 kilometres north of the visitor centre, but there are several areas where the lake depth reaches 150 metres,” he said.

The 3D dataset will lead to a better understanding of the lake’s underwater habitats and how it was formed. Plus it will help ensure safe navigation on the lake and assist future research, such as using the lake for the testing autonomous underwater vehicles.

The team endured wild weather over eight days using a twin-hulled 8-metre research vessel, the RV South Cape, and an uncrewed, remotely operated vessel called the Otter.

RV South Cape was equipped with a PORTUS pole, being a portable carbon fibre sonar mount. The multibeam unit was a Norbit Winghead i80S-Apogee, compact, ultra-high resolution curved array broadband multibeam sonar.

In ultra-high resolution, the Winghead i80S-Apogee has 2,048 dynamically focused beams, which were employed for the survey. Most of the survey was done at 400 kHz but 200 kHz was used for anything below 120 metres.

The team achieved a 1m grid over the deepest parts of the lake, with much smaller gridding size available in the shallower areas. It is anticipated that 10cm gridding might be possible in the shallow areas.

The Otter was able to map in the shallower areas not accessible to larger vessels, and also was equipped with LiDAR technology to map the lake shore.

The Otter USV, made by Maritime Robotics, carried a Norbit Ekinox wideband curved-array multibeam sonar equipped for high density with 1,024 beams. It was used at 400 kHz for the shallow water surveys.

“The mapping is highly detailed and can identify objects as small as 50 centimetres in some places,” said Déplante.

“Along the shoreline, it shows the trees that have fallen into the lake and, in deeper areas, has revealed several mysterious features on the lakebed, sparking curiosity about their origins.”

“While the data does not confirm the presence of a Lake St Clair ‘Loch Ness’ monster, it does offer a powerful new tool for exploring the lake’s hidden depths.

“Importantly, the project provided us with the opportunity for cross-disciplinary training for our team and to integrate the latest technologies into our toolbox to enhance the capabilities we offer the research community.”

The project was headed up by CSIRO’s Engineering and Technology Program in Hobart, with support from the Autonomous Sensors Future Science Platform.