By Vincent van Altena, Jakub Wabiński and Ana Petrović

Navigating an unfamiliar city can be challenging, especially if your vision is impaired.

While navigation apps can guide you from doorstep to doorstep and adapt your route on-the-go, they often fail to inform you about your immediate surroundings. This can lead to practical challenges, such as positioning yourself at a bus stop, and can also result in more dangerous situations.

Moreover, relying solely on an app’s efficiency makes it difficult to get an overview of the transport system’s layout.

Similar issues arise when interpreting local weather forecasts or understanding the composition of the world’s continents.

In all these scenarios, maps play a crucial role in enhancing our understanding of the world.

To help people with visual impairments enjoy benefits of cartography, we gathered more than 30 contributors from around the world and wrote a book about tactile mapping.

Digital cartographic exclusion

Traditionally, it has been cartography’s role to provide context and increase spatial awareness. Maps are essential for, inter alia, understanding landscapes, regional economies and cultures, and geopolitics, offering valuable insights into spatial relationships.

To obtain a bird’s eye view, well-designed maps are indispensable.

DDigital mapping, such as navigation apps and web maps, have become part and parcel of the daily lives of many, significantly impacting individuals’ abilities to spatially orient themselves in the world.

While mobile technology is now accessible to most of the world’s population, potential connectivity issues make navigation apps and web maps prone to failure.

Furthermore, effective use of digital maps requires specific skills that must be acquired, yet education, mobility training and rehabilitation are not equally accessible.

Moreover, access to and use of geographical information are limited by the visual nature of cartography. This particularly affects people with visual impairments (PVI), who must rely on senses other than sight.

Addressing challenges

Our visual capabilities can be compromised by many factors, early or later in life, and symptoms can vary: colour vision deficiency, blurred sight, tunnel vision, or complete vision loss are only a few examples.

Over the centuries, attitudes towards mitigating and remedying the consequences of vision loss have changed. This has had a profound impact on the evolution of education for PVI and support for their training in mobility and spatial orientation.

In the late 18th century, experiments with cartography suitable for haptic perception began. These initial attempts developed simultaneously with braille-like scripts and were tailored to specific contexts, often influenced by particular understandings of vision impairment and haptic perception.

Specifics of haptic perception

For sighted people, it is hard to imagine what it is like when light of day vanishes from your eyes or needing to rely on your other senses for perception. Sighted people can start with an overview picture, which they can immediately begin interrogating for details.

A person with visual impairment, however, has to put in additional effort to arrive at that initial overview.

Their first step is to build an overview from details, which can be perceived by haptic, audible, or — depending on the severity of their vision loss — visual sensations. Haptic perception includes both the senses of touch and proprioception, the position of body parts within space.

When sight is reduced due to some form of vision loss, the information which can be perceived is likewise restricted. This information loss can be partially compensated for or complemented by one of the other senses, but due to functional differences between the senses, the amount and type of information people can acquire from them is not the same.

For instance, the attainable level of detail (resolution) of tactile and visual perception is very different as is the distance required to perceive two distinct but adjacent objects (they need to be placed further apart).

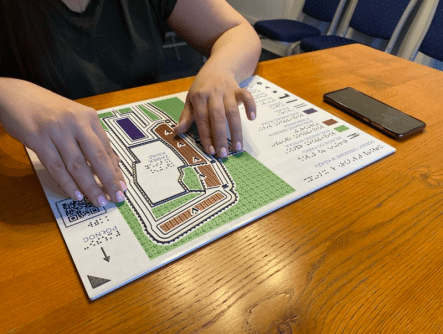

The additional step needed to interpret an image by touch, as well as the restrictions in resolution and distinctiveness, are important design considerations for cartographers who prepare accessible maps for PVI. Tactile maps have to be highly generalised, offering only the necessary information to avoid cognitive overload in the map reader.

Tailormade and the scientific realm

Due to the limited consumer demand, and the fact that PVI are unique in their physical and cognitive challenges and needs, many of the advances in tactile mapping have remained restricted to specific practical contexts or individual academic studies. This explains why these studies have not led to the kind of universal standards that exist in traditional cartography.

Fortunately, this situation is changing. More collaboration is being organised and many new production technologies are now emerging. This brings the solutions within reach of many more map readers with vision impairments.

The tactile mapping book

To collect knowledge on tactile mapping and disseminate this information to a wider audience, a group of more than 30 contributors (many of them affiliated with the ICA and the WGIC) has collaborated on the book Tactile Mapping: Cartography for People with Vision Impairments. It contains contributions from cartographic experts, case studies from practitioners, and personal experiences from PVI.

The book is divided into 11 chapters. The first addresses the system of sight and causes of vision impairments, as well as historical attitudes towards PVI. Subsequent chapters provide insights on the relevance of maps in our understanding of the world and introduce the parallels and differences in perceiving the world by sight and by touch.

They explain how a haptic symbol grammar can be built and how effective use can be made of tactile symbols, discussing the interplay between map design, cognition and generalisation of geographical data.

Finally, the application of new media and technologies, such as 3D printing and multisensory outputs (e.g. audio-haptic media) for tactile cartography are discussed and the book concludes with a reflection on methods for evaluating the legibility and utility of a tactile map for its users.

Throughout the book you will find inspiring personal stories of daily life challenges faced by PVI. It also advocates that it is essential not only to involve the prospective users in all facets of the design process, but also to offer education and training to PVI and educators.

Regardless of whether the use context is global geographic orientation or local mobility training, maps remain useless if their potential readers do not know how to find and use them.

Towards a more inclusive cartography

Both the editors and contributors hope that the book will inspire practitioners to transform conventional maps into tangible devices, thus opening the world of cartography to an often-overlooked audience.

While the book doesn’t offer a singular, definitive solution, it intends to be a guide and springboard for experimentation and development of alternative media for conveying geographical information, thus contributing to an individual’s autonomy.

To quote from one of the personal stories: “With a tactile map of my surroundings, I can be more spontaneous… They help me gain independence and make me feel like I belong.”

***************

The ICA and inclusive cartography

Since the mid-1980s, the International Cartographic Association (ICA) has aimed to broaden cartography beyond visual formats. The former Commission on Maps and Graphics for Blind and Partially Sighted People focused on tactile cartography for people with visual impairments.

In 2023, the Working Group on Inclusive Cartography succeeded it, expanding its scope to include all kinds of marginalised groups. The Working Group aims to transform traditional mapping practices by prioritising inclusion and accessibility. It strives to dismantle barriers that have historically excluded marginalised communities from the benefits of maps.

The Working Group offers webinars, meetings and workshops. Please visit https://inclusive-cartography.icaci.org/ for more information.