RQ-84Z AreoHawk UAV after take-off

The following article was written by Mark Deuter, the Managing Director of internationally regarded but South Australian based aerial surveyors and 3D modellers AEROmetrex. Deuter challenges the notion that RPAS surveys will replace conventional aerial surveys and affirms that UAVs are just another platform for a sensor.

The energy, enthusiasm and the inventiveness that is going into UAV* technology these days is truly remarkable. There has been a proliferation of manufacturers, suppliers, users and conferences promoting the technology. We have all seen stunning video clips and images taken from UAVs – the low altitude aerial perspective enables unique views of a wide sweep of surrounds as well as the foreground focus of attention.

In July 2012 I attended the ESRI International User Conference in San Diego and assisted a UAV manufacturer on their trade exhibit, fielding questions from potential customers of this technology. It was a revelation, not only because of the technology, but because of the reaction of the punters. I could see it in their eyes. Everyone wanted to do this for a job. “Get paid to have fun? I’m in!”

As a long-standing aerial surveyor I have watched the rise of UAVs with an open mind. Indeed the company that I part-own and work for is a CASA-registered UAV operator and we have invested heavily in the technology. We know what it takes to make a good UAV aerial survey and we can show some great examples of our work. However we are in the somewhat unique position of being able to compare the cost-effectiveness and the results of UAV aerial surveying against the latest full-scale aerial surveying equipment and methodology, because we have both capabilities.

I can say right here and now that the concept of UAVs as a platform for aerial surveying is suffering from a typical problem that plagues new technologies. It’s over-hyped.

Yes, you can take an aerial photograph with a UAV. Yes, that photograph can be used to map an area of interest. But no, in 99% of cases you cannot do it as well, as fast or as cheaply as you can with a large-format aerial camera in a conventional fixed-wing aircraft. That may surprise you but it’s true.

With apologies to Ha-Joon Chang, the author of the excellent book “23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism” ** I have set out here 20 things they don’t tell you about UAVs.

SENSOR

Thing #1. A UAV is just a platform for a sensor

A lot of discussion in the UAV industry revolves around which UAV is best. Every manufacturer stridently proclaims the advantages of their system in terms of battery life, stability, payload, range control functions, etc. But hardly anyone acknowledges that a UAV is just a platform for a sensor. We don’t make a big fuss about whether we use a Cessna 441 or a Cessna 404 or a Piper Navajo to fly your aerial survey. To us an aircraft is just a means of positioning a sensor. It’s not about the aircraft, it’s about the sensor.

Thing #2. A small UAV carries a small payload which means small format sensors

There is no doubt that you can cram lots of megapixels into a compact camera or a DSLR these days. But even a 36MP DSLR camera is small format compared to the latest generation large-format aerial mapping cameras, at 360MP or even bigger. Small UAV = small format sensor = lots more runs and photos = inefficient capture.

Thing #3. A $1,000 sensor is not as good as a $1.5m sensor

There are sensors and sensors. Most UAV systems carry small compact cameras to eke out precious payload. More sophisticated systems may be able to carry a DSLR camera. But these are non-metric consumer grade cameras, with uncalibrated lenses, prone to temperature variation, with limited storage on-board and using Bayer-filtered 3-band RGB imaging systems. They are not to be compared with modern aerial mapping cameras which have much bigger formats, separate lens cones for each multispectral channel, often in 4 bands (R,G,B and NIR) along with dedicated panchromatic cones, which have geometrically calibrated lenses with known distortion characteristics, with gyro-stabilised mount correcting level and drift, with almost unlimited storage and extremely sophisticated airborne GPS, IMU and navigation systems. Not surprisingly, a $1000 sensor is just not as good as a $1.5m sensor.

OPERATIONS

Thing #4. A UAV is not unmanned

Strangely, an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle is not unmanned at all. The men/women are on the ground. Hence the new terminology RPAS (Remotely Piloted Aerial System). There are usually two operators, just the same as the aircrew in a light aircraft. Where is the saving?

Thing #5. Labour costs make small UAVs uncompetitive

Do the maths. Don’t forget to include the time and cost of getting the UAV operators to and from the survey area, the time needed to conduct the survey, the costs of accommodation and travel allowances, and the cost of masses of GPS ground control. As well as the salaries for 2 skilled people (UAV operator, surveyor). Adds up pretty quick. We reckon it’s more efficient to get a large-format system in for anything bigger than a few km2, even if you’re right there on the spot with a UAV.

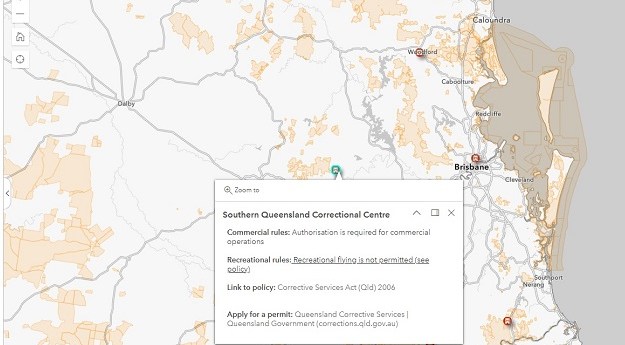

Thing #6. UAVs are justifiably limited by airspace regulations

CASA (Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority) is very concerned about the prospect of an airspace swarming with UAVs and has imposed strict limits on commercial UAV operations. We have already seen one instance in which a UAV operator (not us!) lost control of a UAV which flew across the flight path of a military airport. And one has now hit a jet aircraft in flight.

UAVs may only be operated by CASA-certified operators and can only legally be operated as follows:

- Not above 400’

- Not over a populated area

- Not within 3.5nm of an airport

- Not outside VLOS (Visual Line of Sight)

unless specific approval has been granted. These applications are considered on a case-by-case basis by CASA and the waiting period for a response was out to several weeks last time we applied. Fact is, if you operate legally there are not many places you can fly a UAV commercially.

Thing #7. Line of sight is no more than 500m

Try spotting a small UAV flying away from you. It takes about 15 seconds to completely disappear. Therefore run length is limited to 30s flight time, unless you station observers along the flight path equipped with radios for back-to-base comms. This has been tried. See Thing #5.

Thing #8. You will need formal training to operate a UAV legally

To be qualified as a UAV operator, you will need:

- Basic Aeronautical Knowledge (BAK) or Private Pilots Licence (PPL).

- Radio operators licence

- Manufacturer training on type

- and then pass the CASA exam.

You can’t just take it out of the box and start flying.

Thing #9. A UAV is capable of killing you

Our small UAV system weighs 3.8kg (the same as a brick) and it travels at up to 120km/hr (33m/s). If it hits you in the face at that speed it will decelerate almost instantly, say in 0.1s. No laughing matter.

My high school physics tells me Force = mass x acceleration.

So F = 3.8kg x (33/0.1) m/s2 = 1,254 Newtons. In the face.

Serious injuries have been caused by powerful UAV propellors and, as was demonstrated by Mythbusters recently, a large multi-rotor UAV propeller could sever an artery. There are a number of accounts on the web of unmanned helicopters decapitating their operators. Check your training, your safety systems and insurances. Don’t think they are too small to hurt anyone.

Thing #10. UAVs suffer from local environment effects (especially wind)

UAVs are very small aircraft and subject to forces that would not affect larger aircraft. Wind is especially problematic for small UAVs, and wind is often stratified, ie, much different even at 400’ than it is at ground level. Weather forecasts are usually published for ground level conditions. Can you really keep your UAV on track? Will your UAV be able to grind its way back to base in a 40 knot headwind?

Thing #11. The logistics of UAV operation are problematic

Think again if you are planning to provide a UAV service in remote areas, which if Thing #6 is properly observed, is where you will end up. Do I drive or do I fly to the site? If it’s too far to drive or the roads are rubbish, or don’t exist, perhaps I could get there in a light aircraft, or a helicopter? Wait …

Thing #12. Blurry images cannot be used to generate accurate results

We are sometimes asked to save UAV surveys which are comprised of blurry, badly exposed imagery. Lack of detail destroys the effectiveness of image matching algorithms, resulting in lack of tie points and geometric accuracy. Such surveys are usually unsalvageable and must be reflown.

Thing #13. Eagles hate UAVs

With a passion. The last thing any self-respecting eagle will tolerate is another predator blundering through its territory not even bothering to look up – the arrogance! Eagle hits on UAVs are common. See Thing #14.

ECONOMICS & RISK

Thing #14. The capital cost of a UAV is significant

A sophisticated UAV is likely to set you back anywhere from $30,000 to $100,000. Let’s say you get a bargain at $50,000. What is its useful life? 200hrs? Let’s amortise that cost over 12 months assuming you’re a skilled pilot and can run the gauntlet of crashes resulting in total loss that long. It will cost $260 per hr in capital burn alone. About as much as the total running cost of a Cessna 172.

Thing #15. UAV crashes are common

The stories are mounting. UAVs escaping, getting lost, slamming into mine walls, crash landing, etc, etc. All expensive stuff. What is the life of a UAV system? Who knows? Only as long as your next uncontrolled event.

Thing #16. UAV insurance is hard to get

Not unrelated to Thing #15. UAV hull insurance (the aircraft and payload) is usually uneconomic and most operators insure for public liability risk only. That means a crash is usually a loss borne by the operator, and will add tens of thousands of dollars to your depreciation for the year. Hope you weren’t still paying off that loan. Please tell me there aren’t any UAV operators flying without Public Liability insurance. That would be financial suicide. See Thing #9.

Thing #17. You will need Professional Indemnity Insurance if you offer an aerial surveying service

Don’t even think about offering your services to a mining company or other engineering firm if you don’t really know what you are doing and you don’t have PI insurance. Your clients have too much money at stake. An error in calculation is a recipe for financial ruin. PI insurance is both expensive and necessary.

SKILLS

Thing #18. If you’re not skilled in photogrammetry, you’re not an aerial surveyor

Most registered UAV operators optimistically put ‘aerial survey’ as a work category on their CASA application forms. Aerial photographic surveying is an exact and demanding science. A thorough understanding of photogrammetry is required to offer these services. Photogrammetric qualifications are usually offered as an advanced specialisation of a Surveying Degree. Buying a software package that promises centimetre accuracy does not enable anyone to become an overnight expert. There are many traps for the unwary and industry best practice and university qualifications cannot be ignored.

Thing #19. Airborne GPS and IMU for UAV are not accurate enough for direct geo-referencing

The Airborne GPS and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) technology that has been used in large-format digital aerial cameras since 2005 is the same technology that is used in guided missiles. Not surprisingly, some of it is embargoed by the US State Dept. It’s very sophisticated. The resolution of these measurement systems is very precise and is vital to determining the accurate position and attitude of the camera in flight. While advances have been made in the miniaturisation of these devices for consumer application in smart phones as well as UAVs, they really lack the resolution needed for accurate measurement.

FUTURE

Thing #20. While we’ve all been watching UAV developments, other things are happening

The developments that have taken place in our industry are profound, and we should be very proud of them. But they are not really to do with UAVs at all. They are things like:

- Much more efficient sensors. The Ultracam Eagle Prime, and the A3 Edge come to mind. Huge aerial camera sensors with outstanding capture efficiency and storage.

- 3D models – the base map of the future. Great advances have been made in the accuracy, realism and applications of 3D models during the last 4 years. The transition from 2D to 3D mapping systems is happening faster than you think.

- Automated processing and data extraction from aerial imagery.

These developments are the real direction of the industry and where we should be focussing more resources.

CONCLUSION

The UAV industry is what it is – there is no doubt that UAVs have many intriguing applications in many fields, although we have seen the existing service providers back-pedalling from things like pizza delivery or parcel delivery. At the current rate of development and with the concentration of resources being applied to the industry there is no doubt that further advances will be rapidly made.

But beware of the hype, and remember, in our industry it’s not about the platform, it’s about the sensor.

AUTHOR: MARK DEUTER, AEROmetrex.

Visit the AEROmetrex website for more details and keep track of the blog From High Above for more great content from the AEROmetrex team.

* Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are also known as Remotely Piloted Aerial Systems (RPAS) or simply Drones.

** Do yourself a favour and read this book – it’s another eye-opener.