This article was written by Mark Grant of TERN and appeared in issue 110 of Position magazine.

Honey yields vary significantly between years. Production depends on a wide range of factors, including flowering, weather, bee genetics and hive health and nutrition.

New research has investigated whether machine learning can be used to model the interaction of these factors to predict honey harvests. The results are promising, says lead researcher Tristan Campbell, PhD candidate at Curtin University.

“We’ve successfully modelled a key nectar source for honeybees in Western Australia, the Corymbia calophylla (marri), which produces a high antimicrobial honey variety with significant economic value,” he said.

“The model uses a combination of weather data and remotely sensed vegetation data as well as sap flow meters to assess the physiological impact of daily and seasonal climatic conditions on marri tree activity. It doesn’t include all the variables that influence production, but we plan to incorporate hive data in coming seasons.”

Figure 1: Vegetation height and structure data from TERN used to classify forest cover and height for an apiary site.

November weather key to harvest forecasting

One of the key findings of the work is that honey harvests depend a great deal on the weather at certain times of the year.

For example, Tristan Campbell’s fellow researcher Professor Kingsley Dixon says that a cool November indicates a potentially good harvest in February—the main honey flow period for marri trees. And a hot dry January typically means a poor harvest.

“Good honey harvest years can be predicted to 90 percent accuracy just using November average daily maximum temperature and January evapotranspiration data. Or 75 percent accuracy with just November temperature data,” he said.

“As an apiarist myself, such a model provides the first reliable predictor of a good season two months ahead of time, allowing time to prepare equipment and establish new hives for the coming season.”

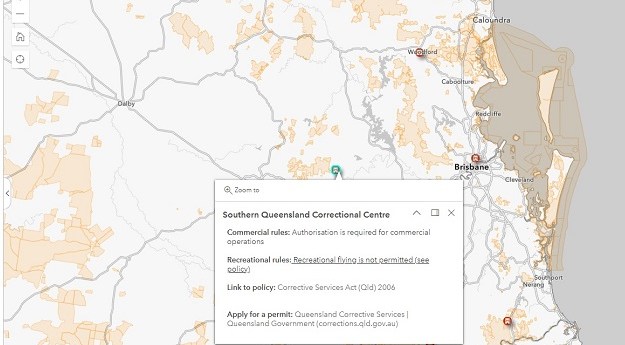

Figure 2: A screen capture of the in-development portal for beekeepers to use the harvest forecast model.

On ground and space-borne data sources

115 datasets were used in the modelling. In addition to a range of weather and climate variables from the Bureau of Meteorology, numerous remotely sensed indices of vegetation were used. These included data on vegetation productivity, photosynthesis, heat exchanges, evapotranspiration and flowering, as well as indices of vegetation greenness and structure.

All the remote sensing data products were sourced via the NASA/USGS AppEEARS service, but vegetation height and structure data delivered by TERN and its partners at the Joint Remote Sensing Research Program were used to provide important contextual information (see Figure 1).

A high-resolution UAV image before and after image classification into flowers, used to calibrate the satellite-derived measure of flower abundance.

Adaptable to other regions and other ecosystem services

While the study focused on honey production from a single species, Tristan Campbell’s PhD supervisor, Dr. Peter Fearns, said that the approach has been designed from the start to be adaptable and could be easily applied to other regions and species.

“Our method uses openly available remote sensing data, so it could foreseeably be applied to other regions where on-ground weather station data and honey harvest data are available,” he said.

“Even without on-ground weather station data, online weather data portals that combine data from multiple weather agencies around the world, like the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute’s Climate Explorer tool, could be used.”

In addition to the prediction of honey harvests, the approach used in the research may be applied to predicting ecosystem services and health as well. This may include forage availability for nectarivores to predict ecosystem resilience for upcoming seasons, or for species that rely on pollinated fruits and nuts, such as the endangered Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus latirostris), that relies on nuts from the marri trees that were the target of the research to date.

Tristan Campbell says that over the coming seasons, data will be collected for other plant species to develop similar predictive models for other honey harvests. Future models will further incorporate TERN-delivered vegetation height and structure data. With the assistance of the Bee Industry Council of WA (BICWA) and ChemCentre, a web portal has been built that apiarists can use to access forecasts and make highly informed management decisions. The beta-version of this portal is currently undergoing testing by the industry and is due to be launched in late spring 2020 (see Figure 2).

If you are interested in further details on the research, please contact Tristan Campbell at tristan.campbell@postgrad.curtin.edu.au.

Stay up to date by getting stories like this delivered to your mailbox.

Sign up to receive our free weekly Spatial Source newsletter.